Toon Dreessen

On Friday, October 1, the City of Ottawa’s Planning Committee and Built Heritage Subcommittee will debate the proposed site plan for the new Civic campus of the Ottawa Hospital, to be located in the Experimental Farm near Preston and Carling. See the BUZZ’s earlier articles about issues surrounding the site, and the Dalhousie Community Associations concerns about the site plan.

In this piece, Ottawa architect Toon Dreessen analyzes the footprint of the proposed campus, and the P3 model under which it’s expected to be built.

This text summarizes a presentation MPP Joel Harden asked me to provide in a town hall session he and Councillors Catherine McKenny and Shawn Menard organized regarding the site of the new Civic campus of the Ottawa Hospital.

It stems from my own concerns about the site selection process and, of course, the challenges of a P3 (Public Private Partnership).

The Site

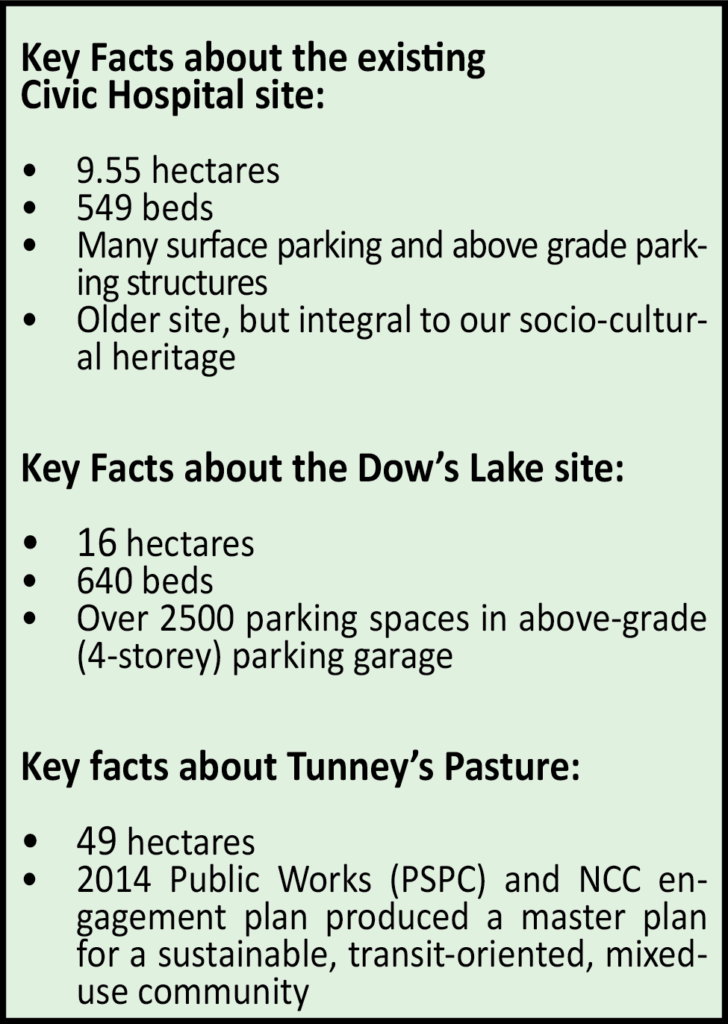

The National Capital Commission (NCC) had, originally, assessed 12 sites based on 21 criteria that included functional size, urban location (close to amenities), emergency access, and other measurable criteria. The NCC also assessed “quality of life” issues such as impact on capital green spaces, cultural resources and heritage sites of national importance, archeological sites, and how the new site could integrate with the community.

Tellingly, the NCC wasn’t tasked with challenging the Ottawa Hospital’s expected land use requirements. It is taken as a given that they would be given all the land they ask for, regardless of what precedents might be set for similarly-scaled hospitals that can use land more efficiently.

The NCC, in the end, recommended the Tunney’s Pasture site. It is geologically stable and flat, and much of the land is already considered a “brownfield” site with existing parking or other buildings that are at or beyond lifespan; major redevelopment of these federal lands will require replacement of sewers, services and some environmental work to address how the site has been used for decades.

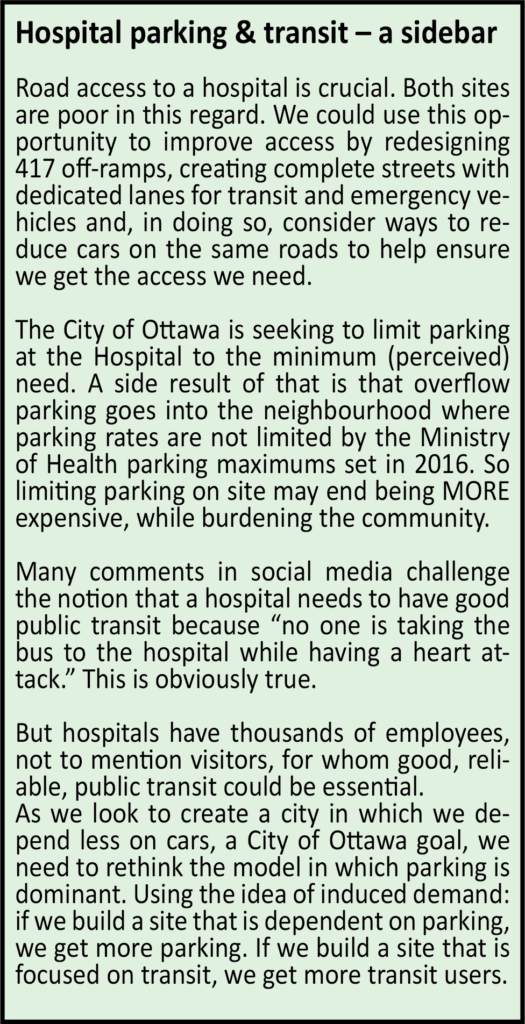

The site has good access to Scott Street as well as the Ottawa River (Sir John A. Macdonald) Parkway. Crucially, it is well served by Ottawa’s multi-billion-dollar LRT investment. It is not well served by Highway 417 access; as anyone who lives or commutes in the area can tell you, Holland and Parkdale Avenues are difficult, to say the least. The recommended site, at 20 ha, is 25% larger than the currently selected Dow’s Lake site. It is interesting to realize that if the hospital had proceeded with this site, and continued to propose a four-storey above-grade parking garage, it likely wouldn’t have seen much opposition, since it would have been part of the overall complex for the hospital.

The NCC announced the preferred site in November, 2016. Then, in what seemed to be an overnight decision, a press conference was held, and the Dow’s Lake site was announced. It is 16 ha in size and geologically challenging. It sits on the edge of a UNESCO world heritage site and is ill-served by transit in its current format. Cost increases to improve the transit connection will either add to the hospital price tag, add to the P3 contract already underway, or be a stand-alone project covered by taxpayers. It will have a significant traffic impact on the community; it is well served by Carling Avenue, but the Prince of Wales/Queen Elizabeth Drive network is significantly smaller than the Ottawa River Parkway. The road access from the 417 is just as poor as the Tunney’s site.

It’s important to note that the existing Civic Hospital site will be redeveloped as a continuation of institutional use. The Heart Institute, which recently received millions of dollars in investment, is unlikely to move until after 2036, based on the Heart Institute’s own press release. Expected continued uses of the current Civic site are likely to include long term care and rehabilitation.

In fact, when the City of Ottawa transferred that site to the hospital in 2000, it included a provision that the land would revert back to the city “if the lands ever cease to be primarily used for non-profit hospital or health care purposes.”

This is important to keep in mind. The Canada Lands Corporation (CLC) plans for Tunney’s include park and open space, housing and mixed use development. As we can see from upcoming images, there is no reason not to think that a new Civic Hospital could be accommodated on a mixed use campus as part of an overall, well planned, land use strategy.

With the current proposal, we will have a net loss of greenspace in the City: the current Civic site remains developed, as does Tunney’s, and we lose the Dow’s Lake greenspace. On the other hand, keeping the current Civic site as developed land, and moving a new hospital to the Tunney’s Pasture site keeps this essential greenspace.

Reading about the Dow’s Lake site, it’s hard to get a sense of what 16ha looks like. What is the impact of this space, and how does it compare to other hospital sites, and other places that do seem familiar? Do we really need 16ha to gain about 100 beds in a new hospital? Do hospitals really need thousands of parking spaces?

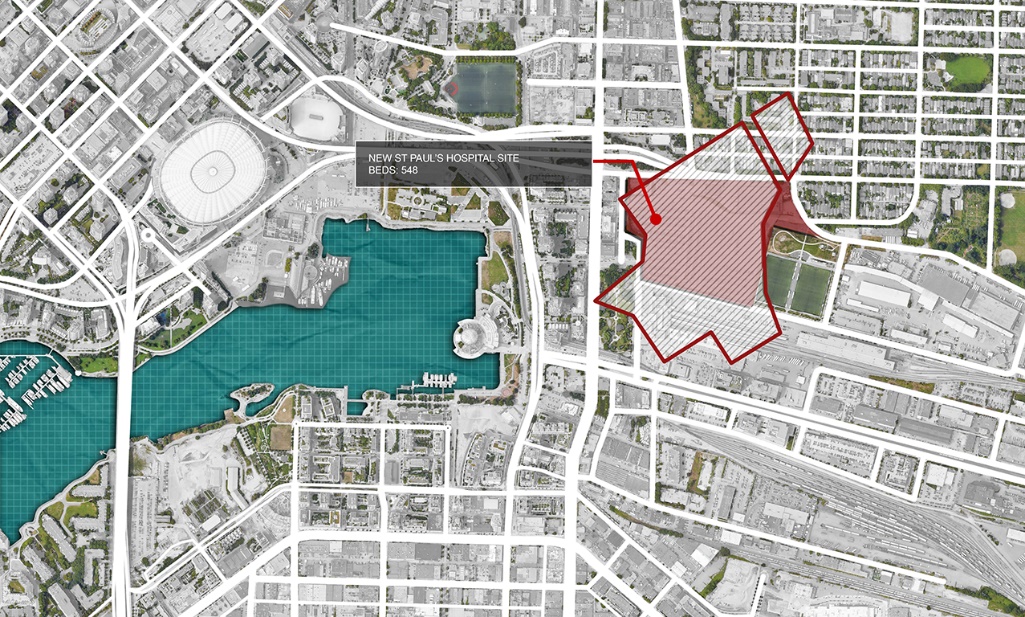

St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver provides 550 beds on a site that is less than a quarter of the area. Currently, plans are underway to build a new St. Paul’s hospital on a 7.4ha site nearby. Maintaining roughly the same number of beds, the new hospital will have 1,170 underground parking spaces on four floors below grade, with an 11-storey hospital above. The 7.4 ha site will also have supporting institutional uses, as well as offices, research facilities, a retail/service area and space for indigenous cultural uses and rental housing for health care workers.

Nearby, the BC Place stadium covers 4ha. Anyone who has been to a game can sense the volume of space. Imagine a space 4 times that large to get a sense of the space the Dow’s Lake site would cover.

Recently built in Toronto, the Bridgepoint Active Healthcare hospital provides 404 beds on a 10 storey structure on just over 4ha, of which 0.82ha is a park. Newly built, recipient of numerous awards for design quality, the hospital provided 2/3 of the same number of beds as our new Civic on about a quarter of the area (or half the area of our current hospital).

Nearby, the Humber River Hospital provided 722 beds on 14 levels with 2 levels of underground parking on a site that is about half the size of the Dow’s Lake site.

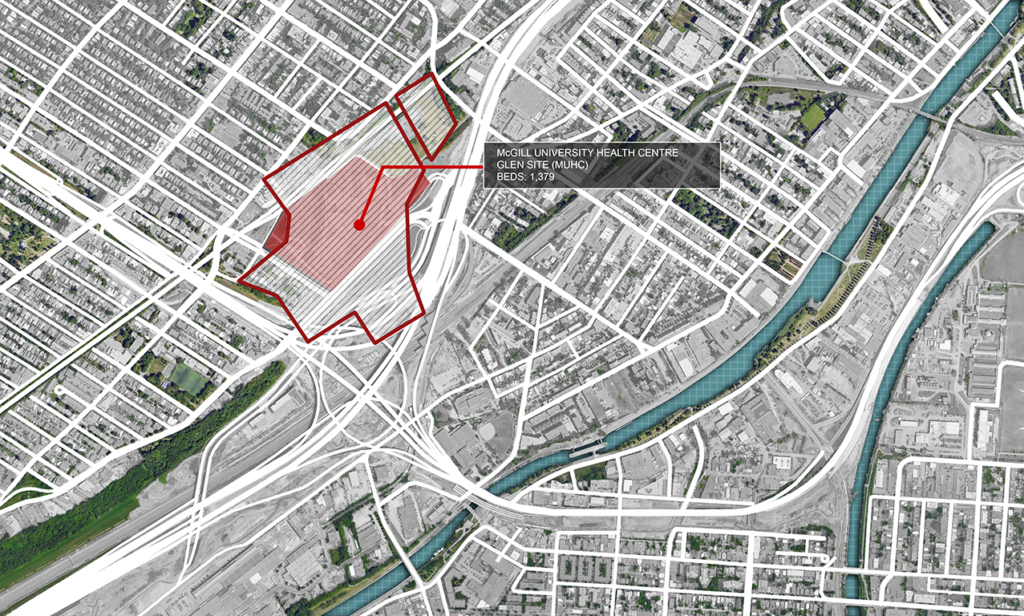

In Montreal, the newly built McGill University Health Centre, Glen Site, provides 1379 beds in the heart of Montreal, connected to transit with a dedicated intermodal station. There are 1582 parking space below grade. Compared to the new Civic, this is more than twice as many beds with 40% of the parking. Parking is free for the first 2 hours and capped at $10/day.

Travelers familiar with New York City know the density of this great city. NY Presbyterian Hospital provides 1000 beds in 2 hospitals on about 1/3 of the site area of the new Civic. Staying in NYC, the new Civic is about half the size of Governor’s Island.

Heading to France, travelers familiar with the walkable density of historic Paris may appreciate the sense of scale of the city. Hotel-Dieu, at 330 beds, is about half the number needed in the new Civic but occupies a fraction of the total site.

Anyone who’s visited the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Le Mont-Saint-Michel, a medieval monastery off the northwest coast of France, can appreciate the scale of this amazing place. The new Civic is about twice the size.

The new Civic is about a third of the size of the ancient walled city of Lucca, Italy. The historic core of Florence, the birthplace of the renaissance and site of the Duomo, is dwarfed by the site area of the new Civic.

Going a little further afield: the new Civic is roughly equal in area to half of the original Disneyland theme park, covering an area equal to Main Street USA, Tomorrowland and Fantasyland. Staying in the land of fun, the new Civic is about quarter of the area of the three islands and all the harbors of Ontario Place.

We’re all familiar with the scale of the great pyramids of Egypt. Some of us have, no doubt, seen them in person. The Great Pyramid of Khufu is about one third of the area of the new Civic.

A 16ha site is large. For a new Civic Hospital, to be built in a city that prizes itself on greenspace and natural landscapes, and aspires to a transit-oriented, zero-carbon future, we can do better than simply hand over this space without rethinking what that means. We know that there are recent precedents nearby that show that we can get the hospital we say we need, even with parking, on less land, making better use of scarce resources.

The Procurement Model

I’m a big proponent of better procurement, so it’s important that we realize what the model is for our new Civic. Key things to keep in mind include not only how it will be built, but what it will look like, and what chances there are we can change this.

The Public Private Partnership model (P3) is the only vehicle used by Infrastructure Ontario (IO) for hospitals. It is also what has brought is the current phase 1 and 2 of the LRT; my blog on this, including links to other articles is here. This has been used by both Liberal and Conservative governments to “leverage value” through models including design-build-finance-maintain; build-finance and design-build-finance. Note that all three models include some means by which the private sector finances the construction.

We have to realize that the images we’re seeing today are not the end result. These are conceptual images generated by a firm hired to produce the exemplar design. Once completed, this sets the stage for construction consortiums to bid on the project. The winner will include a construction firm, financing, architects, and engineers who will attempt to improve on the design while meeting the project intent. Those improvements can mean design innovations but the goal of them is to meet the minimum set out in the contract, increasing the rate of return for the investors. Often, there is no dialogue between the consortium architects and the end user; after it’s finished the end user often feels that, “they got a building, but not the one they wanted.”

Architecture critic Alex Bozikovic, in his 2018 article, noted that the new CHUM hospital in Montreal was competent but not excellent. One of Canada’s leading architects, Donald Schmitt, in the same article, said that P3s are “extremely difficult for architects.” Architect James Brown described the process as, “design by spreadsheet.”

The P3 model isn’t a new problem. The UK invested heavily in the P3 model and has been buying back the contracts because they’ve realized that they don’t work. Ontario’s Auditor General report from 2014 noted that the P3 model cost $8 billion more than if built through the public sector. That was 7 years ago and we’ve continued to pour money down the drain.

Most of that increased cost is from the simple fact that the private sector pays more for financing than the government.

Back in 2014, Barrie McKenna wrote extensively about P3s in the Globe and Mail, noting that taxpayers are often getting raw deal, paying more by “renting money” because it is “politically expedient to defer expenses and avoid debt.”

Based on research on Infrastructure Ontario’s own website, Ontario has built $17-billion worth of hospitals in last decade or so. Eighty-two percent of these hospitals have involved two firms; those two firms alone have built 76 percent of the hospitals with 12 firms sharing the remaining 24% of projects. Effectively, we’ve sole-sourced hospital construction to two firms.

Those two firms decide who the architects and engineers are going to be, based on experience, and minimizing their own risk. It’s nearly impossible for any other firm to get into the market. Hospital design and construction is complex, absolutely, but by concentrating this work in a very small handful of companies, we’ve closed the door on emerging practices and small-to-medium enterprises in favor of large, often multi-national, architecture and engineering practices.

Even bidding on these is expensive. It can cost an architecture firm upwards of a million dollars or more to simply put together a bid. Losing a job means a direct loss to the firm, forcing them to underbid their fees for the next job to stem the loss. As each firm races to put in a lower fee, the opportunity for design creativity, ideas, and options shrinks further.

The loss of opportunity at the design stage is crucial. We’re on a trajectory to tackle critical issues of climate change and provide resilient built environments for a low carbon future.

On the new Civic, we can ask for changes, like increased energy efficiency, but need to see how that fits into a broader context. If we demand, for example, less parking and better transit, will that change the site selection or simply add to the cost of the phase 2 LRT contract while pushing more parking into the neighbourhood? That’s why getting the site right is crucial.

Is Infrastructure Ontario (IO) likely to change their procurement model? No, not unless there is a wholesale change in government and a massive, philosophical, change in IO’s operating model. Even though we know that better procurement models exist, like the Federation of Canadian Municipalities InfraGuide, we’re likely stuck with this broken system for years to come.

We need to see value in how we not only procure the right design, but how we create the city we aspire to. Architecture is political and we need leaders who see that architecture matters. As Edmonton Mayor Stephen Mandel famously said, “The time has passed when square boxes with minimal features and lame landscaping are acceptable. Our tolerance for crap is now zero.” This sparked a revolution in procurement of public sector architecture in Edmonton.

The 1951 Massey Report said, “Canadians are still too little aware of the power of the architect to enrich their lives.” This is still true today; if anything, it has got worse: the role, and ability, of an architect to enrich the process of getting a better Civic Hospital for Ottawa is arguably worse today that it would have been a generation ago.

If we, the people of this city, want a better future, if we want the city we aspire to, we need to change our approach. We need to raise our voices to demand a better outcome, to change what we can, and to rethink the process that is being made despite the evidence that better is possible.

Architecture matters.

Toon Dreessen is an architect and the president of the Ottawa-based practice Architects DCA. He is a past president of the Ontario Association of Architects, and active advocate for the profession of architecture.

2 comments for “Analysis: What will be the real impact of the new Civic Hospital site?”