by Marna Nightingale

I met up with Andrew Kavchak at the Art House cafe, on the same quiet block of Somerset West where, in 1945, Igor Gouzenko’s defection from the Soviet Union marked the beginning—at least for the West—of the Cold War.

Kavchak, a life-long amateur historian, has written extensively about both the Gouzenko Affair his efforts to have it recognized in the place where it happened.

Because of Andrew Kavchak’s determination, two plaques now stand in Dundonald Park—one erected by the City of Ottawa, the other by the Government of Canada—honouring the Gouzenkos and commemorating the events of those world-shaking days.

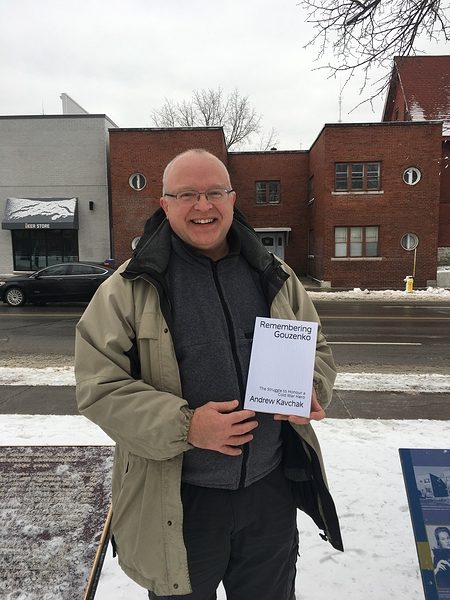

His new book, “Remembering Gouzenko: the struggle to honour a Cold War hero”, is available through Amazon in paperback and as an e-book.

The Gouzenko Affair—the defection of Igor Gouzenko with documentary proof of the degree to which Soviet intelligence agents had penetrated the governments of their supposed allies—upended the wartime alliance between the Soviets and the “the West” just three days after the surrender of Japan.

It all began—and might have abruptly and tragically ended—in a nondescript brick apartment building on Somerset Street, where the Gouzenko family were sheltered and assisted by their Canadian neighbours as the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) attempted to break down their door.

Kavchak’s new book tells the story of those two days as told to Andrew Kavchak by Evy Wilson, the child with whom Svetlana was pregnant during those terrifying days. Sometimes a thriller, sometimes almost a comedy, it’s a story that hovers, always, one mis-step away from tragedy.

511 Somerset was built after a fire in 1941 destroyed the commercial row of buildings that had occupied the block. It’s changed very little in the years since: sturdy, plain, a little blocky, built amid a wartime materials shortage and an urgent need for housing.

Gouzenko, a cipher clerk at the Soviet Embassy, lived from 1943-45 in apartment 4, with his wife Svetlana and their young son Andrei.

Igor and Svetlana had arrived in Centretown in 1943 full of carefully-instilled beliefs about the decadent West, derived from Soviet propaganda of the period. Those notions were immediately challenged by ordinary life in Centretown, where neighbours were friendly and spoke their minds openly and freely.

Around the same time, Gouzenko learned through his work that the Soviet spying apparatus had penetrated even the Manhattan Project—the U.S.S.R was targeting atomic secrets. This he found unsettling.

The federal election of June 1945 was the last straw. Igor and Svetlana were astonished at the political conversations, even arguments, they heard amongst neighbours and read in the papers. The fearlessness with which Canadians criticized their government, even their Prime Minister, was the final proof: the Soviet story of life in the West had turned out to be lies.

In the summer of 1945, the Gouzenkos, now expecting their second child, learned their posting was coming to an end; they would be returning to the Soviet Union.

Igor and Svetlana conducted their serious conversations about their future while playing with Andrei in Dundonald Park-the same park where Andrew Kaychek would later take his own son-for fear their apartment was bugged.

“September 5, 1945, during the long walk from … Somerset Street to Range Road, I came as close to becoming a hero as I ever will.” (Igor Gouzenko)

On September 5 Igor Gouzenko left the embassy at his usual time, with an unusual burden: 109 secret documents he intended to turn over to Canadian authorities.

The documents contained evidence that Soviet spies had infiltrated the Canadian government, and those of other Allied nations, at very high levels. Gouzenko hoped these secrets would both alert the world to its danger and buy Canadian protection for himself, Svetlana, and their children.

Gouzenko was wary, afraid to wholly trust a government agency. He knew the code-names of the traitors and infiltrators, but not their real names, nor the names they were using. So he went first to a newspaper, the Ottawa Journal.

“The first words he spoke were: ‘It’s war. It’s Russia’. Well, that didn’t ring a bell with me because World War II was over and we were not at war with Russia.” Chester Frowde

The Journal’s night editor, Chester Frowde, was skeptical. He listened to the story told, in careful English, by this quiet, frightened man. Then he told Gouzenko to go to the police, or to come back the next day.

Instead, Gouzenko went to the Ministry of Justice, arriving at midnight. The RCMP officers on guard duty turned him away.

That same week, half a world away, Konstantin Volkov, Vice Consul for the Soviet Union in Istanbul, approached British Intelligence offering the real names of three Soviet agents working in Britain.

British Intelligence took him seriously—seriously enough to bring in the head of the Russian Section, Kim Philby, who would be exposed as a Soviet agent in 1963. Volkov was returned to the U.S.S.R. later that week, his head heavily bandaged, on the excuse that he had fallen ill. His exact fate remains unknown.

Kavchak stresses that the Gouzenkos knew the risks they were taking, and the price of failure; knew, too, that once Igor left the embassy they were committed.

Desperately afraid he would be found and killed in the street, Gouzenko returned to the apartment and gave the documents to Svetlana to conceal.

“I could not receive an official from a friendly embassy bearing tales of the kind he had described…” Louis St-Laurent

The next morning Igor Gouzenko returned to the Ottawa Journal and spoke with journalist Elizabeth Fraser. Again, he was turned away.

Desperate, he returned to the Ministry of Justice. He was kept waiting two hours, only to be told the minister, Louis St-Laurent, would not see him.

In those two hours St-Laurent had contacted Prime Minister Mackenzie-King and advised him to take Gouzenko seriously and offer him protection. The PM was reluctant; if what Gouzenko was saying was true, the new, fragile relationship between Canada and Russia would be upturned. If it was false, and Canada took him in, relations would be upturned anyway.

Gouzenko was turned away. But two Mounties were assigned to tail him to see if he was the real thing.

He returned to 511 Somerset, to rest and consult with Svetlana. That afternoon, looking from their window into the park, they saw the two Mounties, watching the building from a bench in the park. Understandably, they mistook them for Soviet agents, and assumed that they were now trapped in their apartment.

They weren’t—then. Later that afternoon, Stalin’s secret police came to Centretown.

As Soviet agents pounded on the apartment door, Igor and Svetlana froze into silence. Two-year-old Andrei squirmed loose and ran noisily across the floor. The efforts to gain entry redoubled.

Desperate, Igor left the apartment via the back door. He found his neighbour, Harold Main, of apartment 5, standing on his balcony. Gouzenko rapidly explained the situation. As the two men spoke a man came up the back lane. They both agreed he looked like a Soviet agent.

Convinced of the danger, Main set off on his bicycle for the police station.

The Soviet agents departed, and the family took refuge with another neighbour, in apartment 6. Main returned with police officers Walsh and McCulloch, who were skeptical of the story, but agreed to keep watch from the park.

If there was further trouble, they said, the family should flick their bathroom light, easy to see from the park, rapidly on and off.

However, according to Kavchak, the officers then, or soon after, left the area. No-one knows when the Mounties left, but they, too, were gone by late evening, when the Soviets returned.

Again they banged on the Gouzenko’s apartment door; Main heard the commotion and came out to say the family had gone away.

In apartment 6, the Gouzenkos flicked the bathroom light—and drew no response. The neighbour in 6 phoned the police, and back came Walsh and McCulloch.

The two policemen found the Soviet agents, who had broken Apartment 4’s lock, inside the Gouzenkos’ apartment. Vitali Pavlov, the leader of the intruders, assured the officers there was no cause for concern. This was an internal, diplomatic matter: they were merely looking for vital papers, they had the Gouzenkos’ permission to enter the apartment, the apartment was “Russian property” anyway.

The police were unpersuaded. If Pavlov had the Gouzenkos’ permission to enter, why did they not have their keys?

Still, diplomats were involved and so the two policemen called for a higher-ranking officer. An inspector arrived and listened to the conflicting stories. He told the Soviets to stay put while he returned to the station to seek further orders.

Instead, the agents departed, and so, shortly afterwards, did Walsh and McCulloch.

The next morning, they returned, this time to escort the Gouzenko family to RCMP headquarters. Gouzenko, at last, was being taken seriously and given shelter. Centretown’s role in the story was at an end—until 1999, when Andrew Kavchak, on parental leave and spending his days at Dundonald Park, playing with his son and looking in fascination at the building where he knew so much had begun, began his five-year quest to see the Gouzenkos properly remembered at the site.

It’s a story shot through with politics at both the global and local levels, and of the personal aftermaths of world-shaking events. It’s the story, too, of his growing friendship with Evy Wilson.

“To be able to say my name and ‘Gouzenko’ is a wonderful thing” Alexandra (Gouzenko) Boire

Life in exile was hard, for the Gouzenkos and for their children. Svetlana’s remaining family in the USSR suffered for the couple’s defection, and the habit of secrecy the Gouzenkos had to acquire never truly left them or their children. Even after the couple’s deaths—Igor’s in 1982, Svetlana’s in 2001—their grave was unmarked until 2004.

Nonetheless, when I asked Andrew Kavchak what he thought the Gouzenkos would feel if they were alive today, he said firmly that neither Svetlana nor Igor ever regretted their choice.

And if anyone would know, it’s him. He wrote the book.